I personally feel that the most serious environmental threat to Louisiana’s coastal fishery as a whole is the menhaden reduction industry, more commonly known at the local level as “the pogey boats”.

Now, if you’re paying attention, then you would have noticed that I didn’t say “Louisiana’s inshore fishery”, but the entire coastal fishery.

No, I’m not talking just about a handful of sport fishermen chasing speckled trout and redfish, but rather everyone. Oyster, shrimp, crab, everyone. Keep reading and I’ll make it clear as to why this is the case.

Quick Note About The Terms “Pogie” and “Menhaden”

Here in Louisiana we have different words for everything. Perhaps it has something to do with Louisiana’s French and Spanish roots, maybe it’s for some other reason I do not know.

For example, we call largemouth bass “green trout” and dolphins are known as “porpoises”.

Neither of those are remotely correct, but it’s what people use here. Well, everywhere else people refer to Brevoortia tyrannus — or Atlantic menhaden — as menhaden, or “bunker”.

But here in Louisiana, where we have a similar menhaden with the taxonomic name of Brevoortia patronus, we refer to them as “pogies”, sometimes spelled as "pogey".

These are also known as “Gulf menhaden”, and I’m not sure that many people even know there’s a different menhaden for the Gulf and Atlantic.

Either way, in this blog post, I will be using the terms pogie and menhaden interchangeably.

I just wanted to clear that up so there’s no confusion going forward.

How Pogie Boats Could Be Destroying Louisiana’s Fishing

Here I aim to explain how the menhaden reduction industry is so bad for Louisiana’s coast, as well as what else it is that people get wrong when addressing this hot topic.

There's a lot more at stake here than just a handful of dead redfish!

If you take time to learn everything I have to share with you in this blog post, then you’d be far more informed on this topic than what most people are armed with, which is usually just repeating what they’ve seen on social media.

What we’ll get started with is why menhaden are so important to begin with. It doesn’t seem that they would be, because of all the things we eat on Louisiana’s coast, menhaden are not one of them.

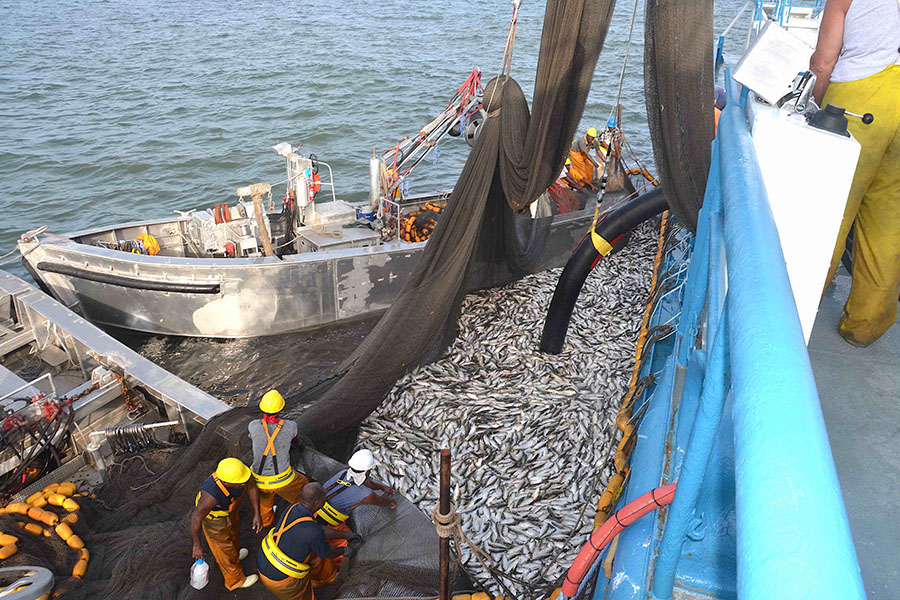

Menhaden are caught with purse seines then vacuumed into a mothership for processing. You won't find these on the menu in restaurants.

Go to any Louisiana seafood restaurant and you’ll see shrimp, crab, redfish, speckled trout, oysters and more on the menu but you won’t see pogies. Not at all.

If you’ve ever handled these fish, you’ll know that they can smell bad. I’ve never been adventurous enough to eat one, but I’ve read that they’re oily, full of bones and don’t taste very good at all.

So why would anyone care what happens to pogies? There are plenty of other fish on Louisiana’s coast that no one cares about and make awful table fare:

So why all the fuss over menhaden?

The answer is that menhaden are a vital link in the food chain. If you can understand why, then you’ll have an understanding of Louisiana’s coastal ecosystem that most do not possess.

But, before jumping into that, I’d like to make a quick announcement:

If we don’t eat pogies, then why are they so important to our fishery?

Menhaden are important in a way that other “rough fish” such as needlefish and hardheads are not. It’s all about what they do for Louisiana’s coast:

I’ll break it down as simply as I can in the following points:

What Pogies Eat Separates Them From All Other Fish

Virtually all life on earth thrives on sunlight, either directly or indirectly. Without sunlight we would all die.

That’s because plants need sunlight to make energy. Then herbivores eat plants to take their energy, then carnivores eat the herbivores to take their energy.

If that’s not crystal clear, then let me try this cow analogy.

The Cow Analogy

Consider that grass grows in places that are well fertilized, well watered and receive enough sunlight. Then cows eat that grass, then we eat the cows.

If you were to remove grass from the equation, then the cows would starve and die off. There would be no more cows, and we’d run out of food and we would starve, too.

Now, obviously this is a gross over-simplification, but that is more or less how it works. Obviously there are other things we can eat besides the cows. But if there were no cows then our alternate food sources would be strained and there would be hard times.

Well, on Louisiana’s coast, the grass would be the algae that grow in the water column. The cows would be the menhaden (which are technically planktivores), and the "humans" would be all the fish that eat the menhaden. Then, obviously, you and I eat those fish.

If you remove the menhaden, you remove that vital link in the food chain and then everything above it comes crashing down.

Even if the effect isn’t immediately apparent, just like in our cow analogy, the ecosystem would still be stressed.

When fish don’t have menhaden to eat they will find something else to eat and, when they do, they will strain — or even break — that other part of the food chain.

This cartoon I found does a pretty good job explaining what happens:

So that’s pretty bad, right? But it actually gets worse. That’s because killing off menhaden brings about something akin to a nuclear winter. I’ll explain:

The Nuclear Winter Analogy

The worst things about nuclear weapons isn’t the initial blast and radiation they create, it’s the nuclear winter that follows.

When a nuclear bomb detonates — especially something really big in the range of megatons — it throws billions of tons of ash and dust and crap into the atmosphere. There it suspends and blocks out that life-giving sunlight for years.

What do you think happens at that point in time? Nothing grows, then there’s nothing to eat and whatever’s left probably has three eyes and glows in the dark anyway.

So, there’s an indirect effect to the detonation of nuclear bombs in our atmosphere that’s worse than the initial direct effect.

Well, when menhaden reduction occurs in the ecosystem, there’s more damage that’s done over the long term, and this is due to the third thing they do for Louisiana’s coast that I listed above: they clean the water.

How Menhaden Clean The Water

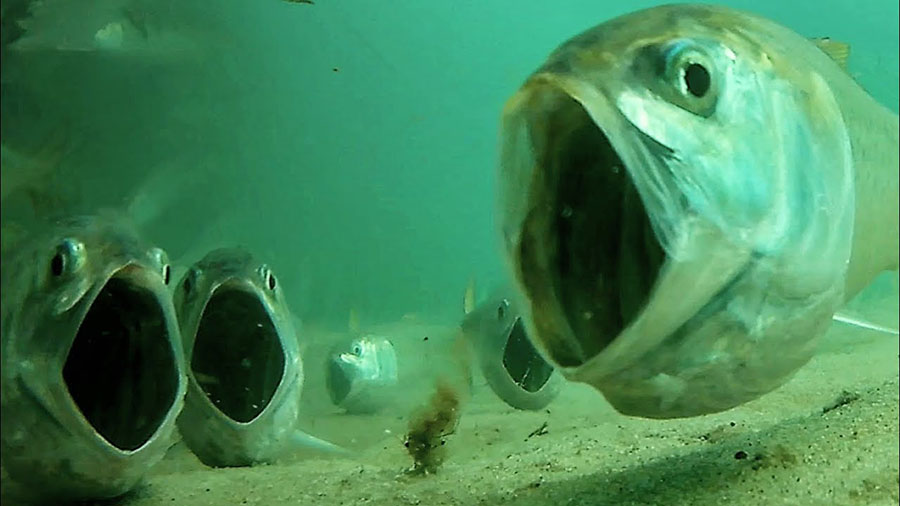

If you’ve ever held a pogie and looked in its mouth, you will see that they do not have teeth like a speckled trout, redfish or bass.

That’s because they’re filter feeders. They filter the water of algae, nitrogen and plant detritus for sustenance.

Pogies can open their mouth wide and filter a lot of water. Photo courtesy of My Fishing Cape Cod.

So, how much water can menhaden filter? Scientists estimate that an adult menhaden can filter as much as four to six gallons a minute.

To put that into perspective, if you filled the Super Dome with water, it would take last year’s catch of menhaden no more than 14 seconds to filter it, probably closer to something like 4 seconds.

For comparison, an adult oyster can filter something like 1 gallon an hour. Yeah, not even close.

How Menhaden Reduction Can Be Harmful To Oysters, Speckled Trout, Redfish & More

The filter feeding of large schools of menhaden clean the water. Any inshore angler can appreciate why that’s beneficial. I mean, it really is that simple, but there are some aspects of that which are not so clear (pun not intended).

So, let me explain the benefits of filter feeding, why everything living in Louisiana’s coastal waters need it and what happens if that filter feeding is removed from the ecosystem.

Penetration of Sunlight

Remember earlier when I mentioned how important sunlight is? Yeah, that’s still in play here. When menhaden filter the water and clean it up, that water is more easily penetrated by life-giving sunlight.

A desirable consequence of this is the creation of more habitat.

Clear Water = More Sunlight = More Oysters

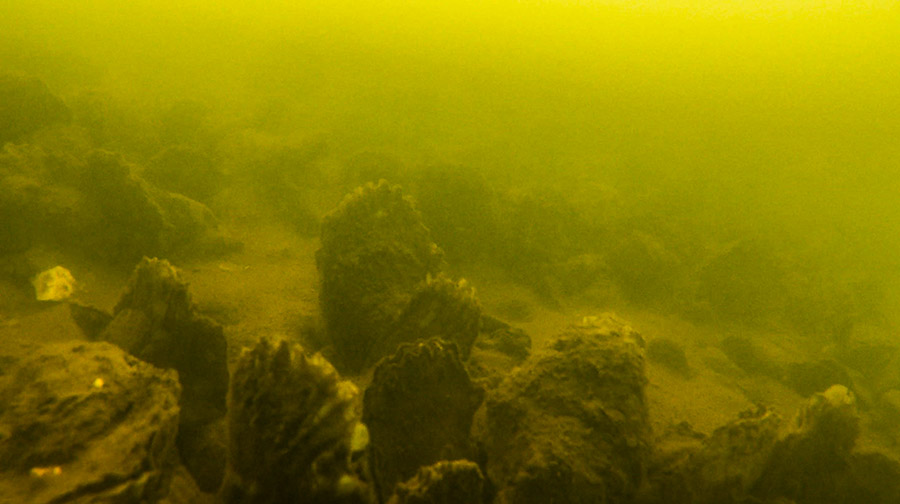

Oysters are also filter feeders that enjoy eating algae. But, unfortunately for oysters, they can’t swim at the surface like menhaden do. They’re glued to the bottom and have to eat whatever flows with the current down there.

So, if sunlight can penetrate to that depth — which amounts to no more than 10 feet — then those oysters will have plenty of algae to eat and will flourish and, with time, build a big oyster reef.

These Biloxi Marsh oysters are surrounded by algae-laden "trout green" water that is about 3 feet deep.

If you have spent any amount of time fishing for speckled trout (or other inshore species) then you know how important that is to finding and catching fish.

But I’ve got Earth-shattering news: oysters don’t grow in the dark.

Go to the bottom of any of these locations and see if you find oysters:

- Seabrook in New Orleans

- Caminada Pass in Grand Isle

- Grand Pass in Dularge

- Lake Campo Pass in Delacroix

You won’t find them there because little to no sunlight penetrates those bodies of water, which range from 20 to 100 feet deep.

Oysters do better in shallower water. If you’re not sure, visit any oyster lease in Louisiana.

The dirtier the water, the shallower oysters have to grow (i.e. two to four feet) and the fewer oysters you have. But if there’s more sunlight that can penetrate the water, in say water that is two to six feet deep, then you’ll have far more real estate for oysters to grow in.

Clear Water = More Sunlight = More Aquatic Grasses

Now that you have a good grasp on how menhaden reduction would harm oysters, you can easily see how overfishing menhaden would do the same for aquatic grasses that grow in the water column.

These are no different from plants that grow above the water’s surface. Just like oysters, they don’t grow in the dark. Surprise!

Still not sure? Take your wife’s favorite potted plant and stick it in the closet for a month. See what happens. That will be a lesson in life-giving sunlight you’ll never forget, and it won’t be coming from the plant!

Aquatic grass like this filters the water and provides habitat for bait and fish.

The more sunlight that can penetrate the water column, the deeper aquatic grass can grow. The most common submerged grass you’ll find in the brackish water of Louisiana’s coast is a type of Eurasion milfoil that also acts as a water filter and provides habitat for the entire food chain.

It’s no secret that the best sight fishing you can do for redfish in the entire world is in the parts of Louisiana’s coast that feature giant mats of aquatic grass.

Visit one and you’ll see a wide variety of bait swimming around to include, but not limited to:

Eurasion milfoil isn’t the only kind of aquatic grass that grows in Louisiana’s saltwater. There’s also turtle grass, which is found in the higher salinity at the Chandeleur Islands and eel grass, which is common on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain.

Grass mats like these are very productive for redfish and even speckled trout.

Go to places like Lake Carencro in Dularge or virtually any pond in Venice and you’ll find a wide variety of grasses that benefit the local fishery.

By now I think you understand the importance of menhaden filter feeding the water column for improved sunlight penetration. But there’s another aspect to clearing the water that goes overlooked:

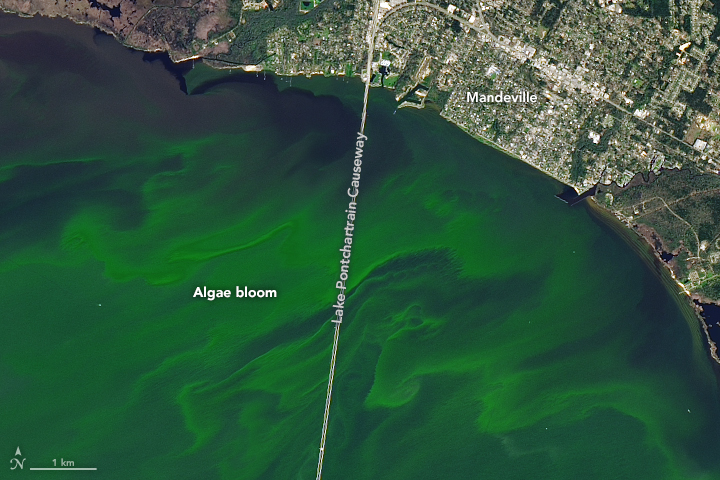

Pogies Keep Harmful Algae Blooms At Bay

Algae that gets eaten cannot possibly reproduce. But if you remove the thing that eats it — in this case: pogies — then the potential for its reproduction to spiral out of control is much greater than it otherwise would be.

This is one way algae blooms occur. And, if the bloom is bad enough, it can create a thick layer of scum at the water’s surface, blocking that life-giving sunlight, depleting oxygen in the water column and pretty much nuke everything in the water.

We got to see this in action during the height of The Freshening in 2019. There was an out-of-control algae bloom in Lake Pontchartrain that was so bad you could literally see it from space.

Now, the nutrient overload from historical openings of the Bonnet Carre Spillway was the chief culprit of that algae bloom. It’s a reminder of how careful we need to be with planned river diversions. But it is nevertheless an indicator of what happens when there’s nothing or very little of anything to consume that algae to begin with.

I’m not sure if millions of menhaden ever populated that range, but I know different kinds of shad could, which are a freshwater cousin of the menhaden and essentially function in the same way as they do.

However, this actual event that happened before our eyes in the not-so-distant past is an indicator of a future without menhaden: we could see similar algae blooms in Lake Borgne, Barataria Bay, Bay Caillou, Vermilion Bay, Breton Sound and many more.

Menhaden boats "making a set" in Breton Sound, Louisiana.

The Menhaden Reduction Industry Could Kill More Than Just Bull Reds

By now it’s obvious that when menhaden are present there’s a positive compounding effect:

But when the menhaden are depleted from the water there’s a negative compounding effect:

Some of these bad things are immediately obvious. One would be the numerous dead bull redfish spotted by anglers in the wake of pogie boats. This has been going on for years and is nothing new, but it seems the frequency of these events could be increasing.

Either way, the spectacle of miles of dead bull redfish floating in the water and washing up on beaches has certainly drawn the ire of the public on social media and at Wildlife & Fisheries Commission meetings.

But what most people fail to see, and certainly don’t talk about on social media, is the overall and long term effect of the menhaden reduction fishery on Louisiana’s other fisheries.

By now you can put two and two together to see what the reduction of menhaden can do to Louisiana’s shrimp, crab and oyster fisheries in addition to damaging our speckled trout, flounder and redfish populations.

The menhaden reduction industry has great potential to harm the commercial and recreational fishermen if left unchecked. Let me be clear: this is not a user group conflict, but an existential threat!

What Do You Think? Would you share this blog post?

So, you got to hear what I have to say about the issue, but what do you think?

What did I miss? What could have been explained better? Am I some curmudgeon a-hole who hates commercial fishing jobs?

Let me know in the comments section below!

I appreciate it whenever anyone takes time to visit my website, whether they agree with me or not! If this is something you would want to share with your fishing friends, then please do so. It's greatly appreciated.

Where You Can Learn More About The Menhaden Reduction Industry

We have yet to see the “nuclear winter” that the menhaden reduction industry can bring to Louisiana’s coast.

While this may seem like Earth-shattering news to many people, it’s actually old news and something that has repeated itself throughout history.

Yes, what’s happening here in Louisiana has already happened on the East Coast in the last century and the one before that.

I could write about it here, but I would rather you read it for yourself from the same source I got it from: H. Bruce Franklin’s 2007 book The Most Important Fish In The Sea.

It details the history of the menhaden reduction industry, its roots in the 1800s, why it was banned along most of the Eastern Seaboard and more.

It’s a great read and a “must have” for every inshore angler’s library.

You can check your local library for a copy or get a copy from wherever you buy books.

I got mine from Amazon, and if you click the button below you’ll be using an affiliate link that supports this blog at no additional cost to yourself. Thank you.

Hello Paula, thank your for taking time to comment. You’re obviously being thoughtful about this beyond the usual rhetoric found in the menhaden discussion, and I’m flattered that someone beyond the realm of inshore fishing has taken an interest in my humble blog.

I’ll admit this topic has not been on my mind as of late, but I will do my best to provide you with as good an answer as I can.

First off, the aim of this article is to make Louisiana’s inshore anglers aware of the menhaden’s role on our coast, specifically in the food web. In my own experience, many do not. They just see the bycatch and take to social media to voice their thoughts. I also wanted to bring up the fact that this issue reaches to the century before last and we can look to that history as a guiding light revealing what will most likely happen here on Louisiana’s coast.

Save for two fishing trips to Grand Isle in April then to Elmer’s Island in June, I have not fished that side of the Mississippi River, nor have I kept in touch with guides I know that way. I’ve been writing more than anything, and utilizing every drop of discipline to do so because if I start fishing then I’m just on the water every day instead of at home writing and getting things done.

I don’t have recent intel for that are to offer you.

Even if I did, it would be hard to say for certain because there are so many other factors at play. There was The Freshening, which we could still be recovering from, a significant improvement in boating and GPS technology that, in my opinion, makes the efforts of inshore anglers that much more effective (but nothing like spotter planes) and, of course, land loss.

I have also heard, and this is strictly hearsay, that the fishing effort put forth by the menhaden industry here in Louisiana was kept at a nominal level to avoid ruffling feathers and inflaming the public. Then, there was a change in ownership, and the new owners wanted to push the envelope, increase catch and improve their bottom line. This coincides with the menhaden reduction industry becoming a spectacle on social media.

As for additional restrictions, I have not given this a lot of thought. I’ve always advocated for them being completely banned like they have been in parts of the Eastern Seaboard. This is after reading Franklin’s book and seeing that there was a clear historical trend of menhaden reduction fishing harming and/or destroying adjacent fisheries through second order effects. Hoping for a different outcome when there’s a clear historical trend is risky, in my opinion.

But, since you asked, removing the spotter plane would help the menhaden, or restrict the spotter plane’s altitude in some meaningful way. I’m not even sure why having a spotter plane in the first place is ethical. I suppose the practice was just grandfathered in. After that, make the buffer zone wider.

Someone who is far more informed than myself and quite the source of knowledge is Captain Ty Hibbs. He is a wealth of information and I’m confident he can provide you with a better answer than I have. I shot you his email just now.

Please reach out if you need anything else. Thank you so much and good luck with your project!

Hi Devin!

I’m an Environmental Health, Climate, and Sustainability master’s student at LSU-HSC in New Orleans and I stumbled upon your blog while looking for a topic for my policy brief project. First, I want to thank you for such an informative blog and wish I found it sooner. Second, I wanted to get your opinion on the revised NOI entailing the expansion of the current ¼-mile no-fishing buffer zone to ½-mile coast-wide with a broader 1-mile buffer added off Holly Beach that was approved/implemented about a month after your post. This revision was an effort to address the issue of industrial menhaden harvesters causing fish spills and abandoned nets/equipment near the coast, but do you think this is sufficient? Have you seen improvement, further deterioration, or no change? Also, what other regulations do you think would help other than banning menhaden reduction industries all together?

Thanks,

Paula

Thank you for chiming in, Jim! I think the best thing Louisiana folks can do for themselves is become part of the civic process. It’s not easy, but it’s the best way to get things done.

I would also recommend for anyone to attend WLF Commission meetings every month whenever menhaden are on the agenda.

Jim, thank you so much for spreading the word. I very much appreciate that. I am unworthy of such great readership! lol But seriously, I appreciate you making the positive effort. I’m just trying to get the word out and get people informed. Again, thank you!

Dave,

Get the Louisiana legislature involved as well as the CCA. Call your local legislative representative for your parrish. Contact the office of economic development to get the economic impact related to Louisiana’s fishing industry which I’m sure will be in the billions of dollars then compare this to the negative impact of netting menhaden. When you get this information, present it to your U.S. Senator Steve Scalese as well as speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, who I believe to be a fine lawyer from Louisiana.

Equally important, call Ted Venker the Editor in Chief of “Tide Magazine” the official publication of the CCA. Several years ago he wrote an article addressing the negative impact of netting in Gulf and coastal waters.

Hopefully this note will be of help to you.

Finally, touch base with Devin Denman, who has significant clout in your state.

Good Luck.

Jim Thompson

[email protected]

Devin,

Thanks for your excellent information related to the importance of Menhaden. Though I’m over here in Alabama, Menhaden are equally important to the extent that I’m forwarding your email to Scott Bannon, Director of Alabama Marine Resources Division.

Additionally, I am today ordering several copies of the book you recommended in order to gift copies to Scott Bannon and Chris Blankenship.Chris is the head of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and was the former Director of the Alabama Marine Resources Division.

Thanks again for your outstanding educational work on the importance of Menhaden in the salt water marine ecosystem.

Best Regards,

Jim Thompson

Thank you so much, Jerome!

We can begin by being aware. Just knowing has us all better off than being completely in the dark. Share this article with your friends. Then, after that, make sure your state representative knows what you think and, when the menhaden issue comes up at LWF Commission meetings, submit a comment against, or show up in person and submit a comment against.

As far as what menhaden are used for: nothing you cannot get from somewhere else for cheaper without damaging our fishery. To my understanding, menhaden products are subsidized by the government at the cost of our fishery.

What can we do? What is menhaden reduction/harvested for? Fertilizer? Fish oils?

Great info Devin, thankyou! Im sharing this post with my fishing friends.